Anthems of Advent

“The joy of every longing heart” through the lens of illustration and a few timeless Christmas hymns

Surrounded by a panorama of torn paper, at least ten different species of chocolate, and books galore for an ambitious New Year’s reading list, I’m staring at the aftermath of yet another (mostly) blissful Christmas in the doldrums of a rainy December 26. The month-long holiday crescendo topped by arguably the best day of the year is a tough act to follow, at least from an emotional standpoint.

The stillness and quiet I very much appreciate, but despite the significance of Christ’s birth inaugurating a new era for mankind, it’s hard to avoid that predictable deflation the next morning. The 26th is a descent back into normalcy, a reentry from that stratospheric enchantment of lights and colors and indefatigable holiday tunes. I’ve returned from age 5 to a melancholy 55 overnight.

Reflecting on this I suddenly wondered if Mary experienced postpartum depression. As a man that condition is one I can know only metaphorically. Yet it seems an apt one for this particular week of the year. We celebrate the baby born in a manger as the Gift he is to us all. Paul, writing to the church in Rome says, “the whole creation has been groaning as it suffers together the pains of labor”. The month of December, if we’re keen to discover it beneath the ubiquitous holiday carnival, is its own metaphor for childbirth. Of course it was one travel-weary woman’s literal story two millennia ago. But we, through the sacrament of Advent, partake in the “groaning” and labor of that imminent arrival.

Though Paul’s metaphor is a reference not to Christ’s birth but to our awaiting his second arrival, it certainly seems fitting for more than one context. Advent, like it’s cousin Lent, stirs the cauldron, bringing something to the surface that modern life keeps repressed— a rawness and honesty about our true state and the weight we carry around in our hearts. But this honesty, however unsettling, feels somehow.. fresh. Once all the gifts were opened and the glitter settled this year I found myself still savoring the richness, even the anticipation of the previous days and weeks. I’m sure Mary was glad to get past the birth, but did she miss having this tiny but incomparably immense life growing daily within her, his secret movements known only to her— a bond they alone shared?

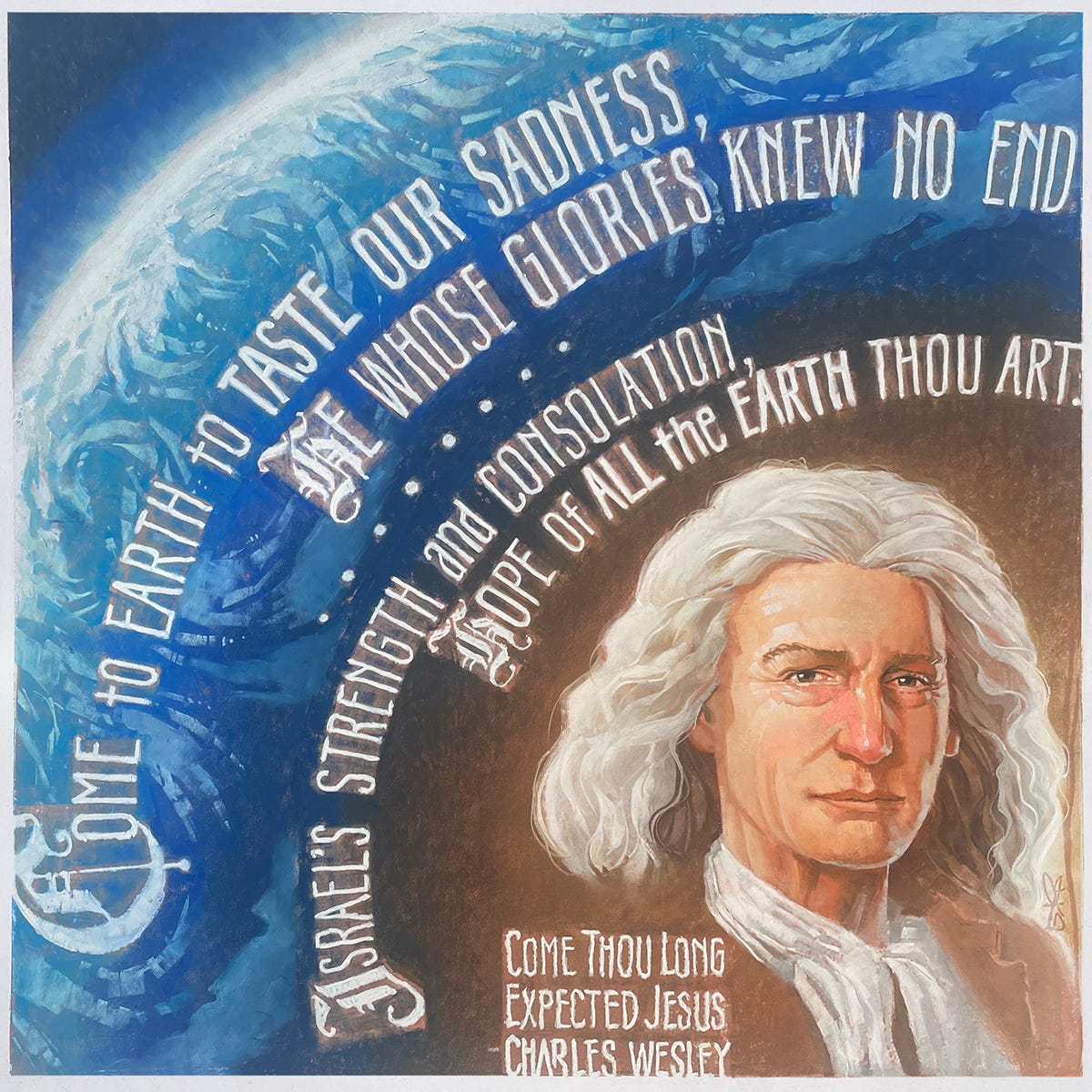

The meaning of Advent is most accessible through the music and poetry of hymns handed down over generations from the minds and inspiration of saints who grasped the beauty and profundity of the season, setting it to verse. These hymns of December are like pebbles in a coming avalanche of grace and wonder. My (above) illustration was a visual expedition into the bittersweet glory that is Advent, and I’m continually surprised by the depth it lends anew each year to the experience of Christmas.

Charles Wesley (1707-1788) penned over 6,500 hymns— yes you read that correctly— including the rousing Hark the Herald Angels Sing and one that has long pierced my heart, And Can it Be: “He left his Father’s throne above, so free and infinite his grace, emptied Himself of all but love, and bled for Adam’s helpless race. Amazing Love, how can it be that Thou, my God, should die for me?” That hymn and his 1744 Christmas classic Come Thou Long Expected Jesus encapsulate the gospel as only great poetry can.

In 2020 this illustration was just a small sketchbook thumbnail as part of a portrait series of various influential people, past and present, integrated with hand-lettered quotes of theirs. Worshiping during Advent that year I was moved by its lines: ”Come to earth to taste our sadness, he whose glories knew no end”. Almighty God has left glories and riches untold to “taste our sadness”, making it his very own, not merely by proxy as a parent who “shares” the pain of a hurting child, but drinking deeply the cup of our suffering, taking it unto himself. “He made him who knew no sin to be sin for us, that in him we might become the righteousness of God.” (2 Cor 5:21) And in Isaiah 53:3 he is “despised and rejected, a man of sorrows, acquainted with grief”.

I recycled the sketch this year when our worship arts director issued a call to the artists in the church to contribute Advent related work. With no other takers there was plenty of wall space, so I also included “glorified” sketches (ie. in color and greatly enlarged from their original 5x8 moleskin format) of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Eleanor Hull.

Wesley’s hymn addresses the hint of sadness, weight, and longing historically intertwined with the Christmas season. In the words of JM Neale’s O come O come Emmanuel a century later, Israel, captive and in need of ransom, "mourns in lonely exile”— not geographically as had indeed overshadowed its recent history but in spiritual bondage, an exile of the heart: estrangement from God Himself. As Neale pleads in the lesser known verse 2, “..Free Thine own from Satan’s tyranny; from the depths of hell Thy people save and give them victory over the grave”. Then follows the refrain, an exhortation to rejoice, as this victory and liberation is imminent and inexorable.

Like Neale, Wesley was a master at drawing attention to the paradoxes of God’s salvation—His grace and love for a fallen and corrupt humanity. Advent is a time when we look squarely at this, our “human condition”, taking ownership of it. Indeed it is only against the backdrop of an acute and sober recognition of our cosmic state that we can truly comprehend what it means that Christ has come. Consider another stanza from And Can it Be: “Long my imprisoned spirit lay, fast bound in sin and nature’s night”. Humanity finds itself pining, yearning, not merely for deliverance from earthly woes— poverty, foreign occupation, the entropy of a cosmos in decline, but the ancient Curse itself which infects every human heart: “From our fears and sins release us”. Out of this darkness arises the stubborn sentiment of hope directed heavenward. This is the heart of Advent. “Hope of all the earth Thou art.”

I took some liberties with Wesley’s likeness as he’s typically depicted a bit softer, likely in keeping with the neoclassical tradition (in Britain and Europe) of “Grand Manner” portraiture, which emphasized such noble qualities as sophistication and education. Though Wesley was indeed a scholar, educated at Oxford and with his brother John cofounding the Methodist movement within the Church of England, he certainly wasn’t homebound. He traveled throughout Britain spreading revival through his “Methodical” practices of prayer and theological study along with his talents of musical composition and teaching. He even sailed to America in the 1730s serving as a garrison chaplain (enduring exhaustion and despair) and later married and had eight children (only three survived).* So despite the idealized aesthetics of neoclassicism, I imagined Wesley a bit more weathered. After working live on a color study during an earlier Advent service I decided to soften his (unintentionally) stern expression a bit from my initial quick sketch.

The dichotomy of darkness and light in Advent is more than eloquent metaphor. The coming of Christ represents the very dividing line between the two— the moment when night gives way to the dawn, when the Light of men, “born a child and yet a king” arrives to shatter the dreary darkness of sin and death. Again, JM Neale: “Disperse the gloomy clouds of night, and death’s dark shadows put to flight.” (JMN —Emmanuel) For my illustration it seemed fitting to set as the backdrop to these exquisite lyrics that very threshold, the radiant glow of earth’s “terminator”, a daily reminder of the coming dawn of eternity, when the “Sun of Righteousness” arrives, “light and life to all He brings, Risen with healing in His wings.” (CW —Hark)

Unfortunately a truncated version of the hymn is more commonly sung, eliminating verses 2 and 3. Wesley brilliantly connects the end of each verse with the beginning of the next, suggesting an unfolding chronology that is lost in the shortened version. First we see the prophetic references of “Israel’s strength and consolation” and “Thou promised Rod of Jesse”. Then we are presented the nativity: “Born within a cattle stall” and “O’er the hills the angels singing news, glad tidings of his birth.” Finally Wesley proclaims Christ’s triumph over sin and death resulting in our sharing in the very glories He forsook to condescend and save mankind. He ends it with a theological tour de force ranging from the first and greatest commandment: “Rule in all our hearts alone” to the restoration of humanity through the shed blood of Christ: “By thine all sufficient merit, raise us to Thy glorious throne.”

Come Thou long expected Jesus is the Gospel set to verse, redemptive history clothed in a truly sublime and stirring hymn. Likewise the classics O Come, O Come Emmanuel and Come, O Redeemer Come also cast heavenward this heavy-hearted plea: “Come.” ..And the great news is.. He did. As we bask in the afterglow of Christmas, reluctantly turning to face another January, we have reason to rejoice, not in a plethora of material treasures, but in the Gift of Emmanuel— God with us. “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us.” (John 1: 14) Christ has come!

One final 18th century favorite, this one by John F. Wade, flips the entreaty to us: “Oh come, all ye faithful, come let us adore him, Christ the Lord.” God is here, and we’re beckoned to seek him. We face the days ahead, not sullen or wistful, not starting from scratch as if December never happened, but in perfect continuity with it. Bonhoeffer compared life in his prison cell to Advent.** We still await our ultimate liberation from sin and death. But no longer must we grope about in the darkness. We walk in the light— light that darkness has neither understood nor overcome. “Go to him your praises bringing, Christ the Lord has come to earth.”

*Encyclopaedia Britannica; National Gallery of Art; Wikipedia; BBC; Thomas Jackson, The Journal of Charles Wesley; John Vickers, A Dictionary of Methodism in Britain and Ireland; Nicholas Temperley, Music and the Wesleys

**God is in the Manger, Reflections on Advent and Christmas Westminster John Knox Press

I love the hymns of C. Wesley and dislike the way so many churches now have gone to “contemporary” style services, which doesn’t move me to worship our Lord. Thank you for writing this piece and I love the portrait too.

“These hymns of December are like pebbles in a coming avalanche.” Yes, that is exactly how Advent feels to me. Our daughter’s middle name is Earendel after the “Daystar” mentioned in O Come O Come Emmanuel. We sing it nightly leading up to Christmas. It’s just a trickle of the Christmas spirit when all the radio stations and stores crank it to the max. We want it to feel a little haunting in the darkness just before bed. Thats Advent!